The Man in the Room: Why Nasubi’s Nightmare Still Matters

A Cross-Cultural Dissection of Fame, Suffering, and the Cameras We Don’t Look Away From

If you have been on the internet long enough, you have probably heard whispers about a show where a man was locked in a room, stripped of his clothes, and forced to survive by winning sweepstakes. What many people do not realize is that it was not a meme, it was not an urban legend, and it was not exaggerated internet folklore. It actually happened.

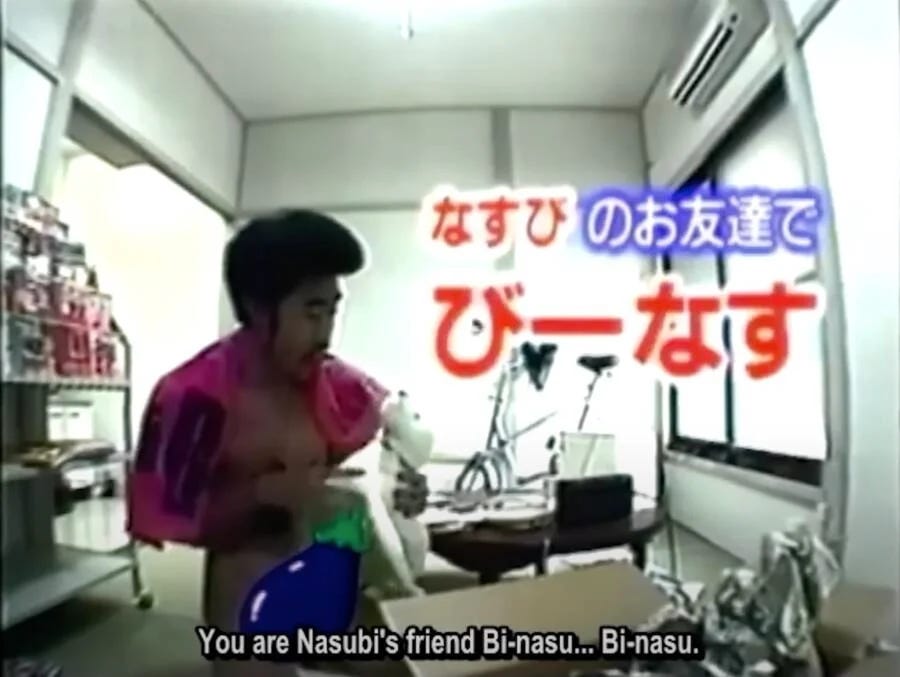

In 1998, a struggling Japanese comedian named Tomoaki Hamatsu, nicknamed Nasubi, which means “eggplant” in Japanese due to the shape of his long face, was selected to participate in a segment called A Life in Prizes. He believed it was just a pilot project. He thought the footage would only air if the show was greenlit. Instead, his experience was broadcast to millions of viewers across Japan every week for over a year.

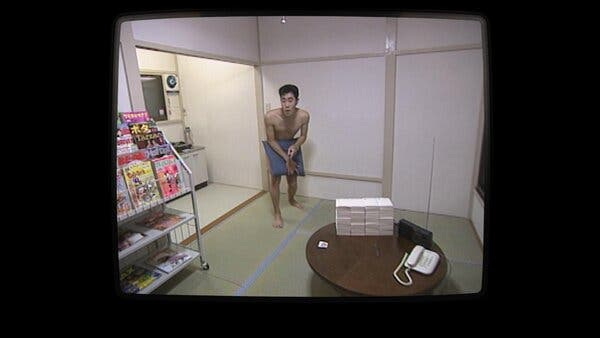

He lived alone in a small apartment, completely naked, with no food, no clothes, and no contact with the outside world. His only method of survival was entering sweepstakes. If he wanted to eat, he had to win food. If he wanted to wear clothes, he had to win them. Even toilet paper required a contest entry and a stroke of luck. Unbeknownst to him, he had become a national sensation. People tuned in weekly to see if he had won rice, socks, or instant noodles. He was not a contestant in the traditional sense. He was not competing. He was not playing a game. He was enduring something that should never have been classified as entertainment.

You almost cannot believe that something like this happened until you step back and examine how differently countries think about fame, dignity, and the function of entertainment. In the United States, celebrities are often treated like distant royalty. They are criticized and memed and placed under a microscope, but they always retain a kind of stylized distance. Their breakdowns are choreographed. Their suffering is polished. We are allowed to look, but we are never allowed to see anything unfiltered. Reality television in the West is built to simulate humility without ever allowing actual humiliation.

Contrast that with East Asian media, and the differences become even more revealing. In Korea, pop idols are revered and adored, but that adoration comes with a demand for vulnerability. Stars are expected to cry on camera, share embarrassing stories, and show the messiness of their lives on variety shows. The performances are structured, but they serve a purpose: to reassure the public that the idol is still human. It is not cruelty. It is intentional softness. The audience needs to see a few cracks or they will not believe the perfection.

Japan’s approach, especially during the 1990s, was something else entirely. Celebrity status was not handed out for free. You had to earn it. And the way you earned it was through submission to absurdity, exposure to discomfort, and a willingness to suffer publicly for the camera.

Both Korea and Japan build their celebrity cultures on admiration, but the way they extract access to that admiration is fundamentally different. In South Korea, stardom is carefully maintained, but the moment a celebrity enters a reality format, they are asked to reveal their softer side. Programs like Running Man, I Live Alone, and The Return of Superman invite A-list idols into slapstick scenarios. Members of BLACKPINK are shown crawling through obstacle courses. Members of BTS are filmed struggling to boil ramen or looking embarrassed in pajamas. These are not acts of cruelty. They are calculated moments of humility. If you want to remain loved, you must allow yourself to be seen. There is tenderness in that expectation, but also strategy. The contract is clear. Perfection must be followed by imperfection. It is the full cycle of visibility.

In Japan, the contract was different. It was older, more brutal, and less concerned with image management. Variety shows like Takeshi’s Castle or Gaki no Tsukai were not merely silly distractions. They were structured as trials. Contestants were dropped into mud pits, smacked in the face with rubber bats, or punished for laughing at the wrong time. These shows were not malicious, but they were extreme. Being on television meant being willing to endure. You did not arrive on screen to be praised. You arrived to be tested.

By the late 1990s, Japanese variety television had entered a new phase. It was no longer just entertainment. It was a public arena of extremity. Producers were not looking for charm. They were looking for reaction. They did not want contestants who could win. They wanted subjects who would suffer. Absurdity was king. Discomfort was the medium. The line between comedy and cruelty became not just blurry but celebrated.

Takeshi’s Castle launched participants into padded obstacles. Gaki no Tsukai created entire storylines around not laughing while surrounded by outrageous setups, where a single smirk might result in a slap, an explosion, or another layer of ridiculous pain. These shows were loud, messy, and hilarious. But beneath the slapstick was a quiet truth. To be on TV in Japan, especially as an unknown, meant you had to sacrifice your comfort. That logic set the stage for Susunu! Denpa Shōnen. And it prepared the public to accept A Life in Prizes not as an ethical breach, but as compelling entertainment.

Nasubi was not famous when the show began. He was twenty-two years old and chasing a dream of making it in comedy. He signed up thinking this might be his break. He had no idea what he was stepping into. When the producers blindfolded him and placed him in a barren apartment, they took away more than his clothes. They took away his orientation to time, place, and reality. His only tools were a stack of sweepstakes magazines and a pen. He had no clocks. No food unless it was won. No clothing unless he could secure it through contest entries. His nudity was masked on screen with a cartoon eggplant, but everything else was raw and unfiltered. For the first few weeks, it was easy to write off the format as absurd.

But as the weeks stretched into months, the producers escalated the conditions. They raised the prize thresholds. They handed him mismatched rewards. A console without a monitor. Rice but no pot. At one point he won a bicycle. He had no street to ride it on. And just as he started to make progress, they moved him. Blindfolded again. Disoriented. Placed into a new apartment with new rules and harder odds. He had to start over. He had to relearn how to survive in silence. All of this played out live. No scripts. No warnings. No context.

In a later interview, Nasubi admitted that he no longer felt mentally stable. He said it felt safer to stay in the room than to return to normal life. What he did not know at the time was that he was already famous. His silent struggle had become a national obsession. Seventeen million people were watching his isolation each week. The producers never paused the broadcast. The show never acknowledged the mental toll. It was never reframed as a crisis. It was simply entertainment. In 2024, Hulu released The Contestant, a documentary chronicling Nasubi’s experience.

For many viewers outside of Japan, this was the first time the full story had come into view. It felt like a fictional story. People compared it to Black Mirror or The Truman Show. But it was not fiction. It was real. And the most terrifying part was not that it happened. It was that people watched. They watched with fascination, with amusement, and with investment. They did not see a man being slowly broken down. They saw a character overcoming absurd odds. There was never a formal apology. Tsuchiya, the show’s producer, once referred to himself as the devil. Even now, he defends the project as a piece of art. Nasubi has said that he still cannot fully forgive him.

Nasubi at a special event at NeueHouse on April 24 in New York City. Credit: Stephanie Augello/Disney

And yet, somehow, he found a way forward. After the 2011 Fukushima disaster, Nasubi turned his fame into action. He supported relief efforts. He showed up for communities in pain. He turned his personal trauma into public service. He found peace not by erasing the past, but by transforming it. He said that instead of regretting his story, he would use it to create something better.

So what do we do with all of this? In the West, we protect our celebrities from humiliation unless they are comedians who volunteer for it. In Korea, we choreograph vulnerability and ask our idols to show their messiness on cue. In Japan, they once built a show around a man’s psychological collapse and broadcast it as light entertainment. There is no system without flaws. There is no version of fame that is clean.

The more important question is not which system is better. The real question is what our favorite kind of reality TV says about us. Somewhere between Nasubi’s hunger and the Kardashian confessionals, somewhere between the quiet breakdown in a locked apartment and the loud confessions on a pristine soundstage, there is a mirror. We have all been watching. The question is whether we are ready to look into it.

🧭 Companion Publication: Explaining NahgOS

📐 About the Architect

Welcome to The Architect's Quarters

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgcorp/p/welcome-to-the-architects-quarters

⚔️ About The Arena

Would You Step Into the Arena?

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgcorp/p/would-you-step-into-the-arena

💻 NahgOS Tech and News Index

Welcome to the NahgOS Room

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/welcome-to-the-nahgos-room

🔬 Science Journal Publications on NahgOS Technology

1. Structure Under Pressure: Measuring Hallucination

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/structure-under-pressure-measuring

2. Structure Under Pressure: Engineered Containment

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/structure-under-pressure-engineered

3. The Mirror That Spoke Back: Recursive Realities

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/the-mirror-that-spoke-back-recursive

🧠 NahgOS Supporting Theory

Welcome to the Theory Room

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/welcome-to-the-theory-room

🔐 NahgOS Public Runtime License

👉 open.substack.com/pub/nahgos/p/nahgos-public-runtime-license-and-bd7

wow, this is wild. I never actually knew the full story!

I still can’t believe this actually happened!!